birth: February 20, 1894

location: Navarro County, Texas

death: January 28, 1978

location: Corsicana, Navarro County, Texas

father: John Ishom Bonner

mother: Martha Britton

spouse: James E. Cox

1910 census

marriage to James E. Cox - 1913

1920 census

1930 census

1940 census

death

burial

children with James E. Cox:

Emmie Mae Cox - 1914

Violet Lorene Cox - 1915

Ola Jewel Cox - 1917

Boy Cox - 1920

Lloyd H Cox - 1922

Robert Lee Cox - 1923

Brownsboro School Board Shooting - 1960

Friday, May 15, 2015

Cumi Cox - 1940 census

1940 census

location: Corsicana, Navarro County, Texas

date: April 24, 1940

Cumi Cox head female white white 47 widowed Texas farmer

Emmie Cox daughter female white 25 single Texas laundress

Jewel Cox daughter female white 23 single Texas laundress

Robert Lee Cox son male white 17 single Texas

Jimmie Cox daughter female white 11 single Texas

Miller Chandler son-in-law female white 24 married Texas

Violet Chandler daughter female white 24 married Texas

Elizabeth Cox sister-in-law female white 56 single Texas

"United States Census, 1940," index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K4SN-VFW : accessed 15 May 2015), Emmie Cox in household of Cumi Cox, Ward 2, Corsicana, Justice Precinct 1, Navarro, Texas, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 175-3, sheet 25A, family 555, NARA digital publication T627 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2012), roll 4112.

Cumi Cox - 1930 census

1930 census

location: Navarro County, Texas

date: April 25, 1930

Cumi Cox head female white 37 widowed Texas farmer

Emmie Cox daughter female white 17 single Texas

VIolet Cox daughter female white 14 single Texas

Jewell Cox daughter female white 12 single Texas

R L Cox son male white 6 single Texas

Jimmie M Cox daughter female white 1 11/12 single Texas

Lizzie Cox sister female white 46 single Texas

"United States Census, 1930," index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:HFR9-42M : accessed 15 May 2015), Emmie Cox in household of Cumi Cox, Precinct 1, Navarro, Texas, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 0011, sheet 13A, family 283, line 14, NARA microfilm publication T626 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2002), roll 2379; FHL microfilm 2,342,113.

Jim Cox - 1920 census

1920 census

location: Navarro County, Texas

date: January 6, 1920

Jim E Cox head male white 26 married Texas farmer

Cumi T Cox wife female white 25 married Texas

Emmie Mae Cox daughter female white 5 single Texas

Violet L Cox daughter female white 4 3/12 single Texas

Ola J Cox daughter female white 2 4/12 single Texas

Lonie N Cox mother female white 63 widowed Texas

Lizzie M Cox sister female white 35 single Texas

"United States Census, 1920," index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MH13-FY8 : accessed 15 May 2015), Cumi T Cox in household of Jin E Cox, Justice Precinct 1, Navarro, Texas, United States; citing sheet 2A, family 40, NARA microfilm publication T625 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,821,836.

location: Navarro County, Texas

date: January 6, 1920

Jim E Cox head male white 26 married Texas farmer

Cumi T Cox wife female white 25 married Texas

Emmie Mae Cox daughter female white 5 single Texas

Violet L Cox daughter female white 4 3/12 single Texas

Ola J Cox daughter female white 2 4/12 single Texas

Lonie N Cox mother female white 63 widowed Texas

Lizzie M Cox sister female white 35 single Texas

"United States Census, 1920," index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MH13-FY8 : accessed 15 May 2015), Cumi T Cox in household of Jin E Cox, Justice Precinct 1, Navarro, Texas, United States; citing sheet 2A, family 40, NARA microfilm publication T625 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,821,836.

Talitha Cumi Bonner and Jim Cox - marriage

"Texas, County Marriage Records, 1837-1977," index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QV1C-MNN3 : accessed 15 May 2015), Jim Cox and Cumi Bonner, 13 Jul 1913, Marriage; citing Navarro, Texas, United States, Citing county clerk offices, Texas.

Talitha Cumi Bonner Cox - death

"Texas, Deaths, 1977-1986," index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:KH3Z-B7K : accessed 15 May 2015), Talitha Cumi Cox, 28 Jan 1978; citing Corsicana, Navarro, Texas, United States, 12856, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Austin; .

Tuesday, May 12, 2015

Annie Ruth Colley

birth: 1911

location: Texas

death: 1978

location:

father: James Jonathan Colley

mother: Rosa Adrian

spouse: Charles Archie Thompson

spouse: Robert Clarence West

spouse: Johnny L Fletcher

children with Charles Archie Thompson:

Dorothy Nell Thompson - 1927

Jimmie Rose Thompson - 1928

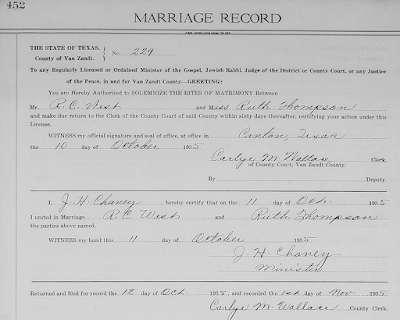

Annie Ruth Colley Thompson marriage to Robert Clarence West

location: Van Zandt County, Texas

date: October 11, 1935

"Texas, County Marriage Records, 1837-1977," index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QV1H-P5FL : accessed 12 May 2015), R C West and Ruth Thompson, 11 Oct 1935, Marriage; citing Van Zandt, Texas, United States, Citing county clerk offices, Texas.

James J Colley - 1920 census

1920 census

location: Ben Wheeler, Van Zandt County, Texas

date: January 20, 1920

J J Corley head male white 41 married Mississippi farmer

Rosie Corley wife female white 38 married Texas

Ruth Corley daughter female white 8 single Texas

Jim V Corley son male white 4 8/12 single Texas

Sylvan Philen stepson male white 22 single Texas farmer

Sylvan Philen stepson male white 22 single Texas farmer

"United States Census, 1920," index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MC9L-D1F : accessed 12 May 2015), J J Corley, Justice Precinct 7, Van Zandt, Texas, United States; citing sheet 10A, family 184, NARA microfilm publication T625 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,821,854.

Charles Archie Thompson - 1930 census

1930 census

location: Ben Wheeler, Van Zandt County, Texas

date: April 15, 1930

Charles A Thompson head male white 26 married Texas farmer

Annie R Thompson wife female white 19 married Texas

Dorthy N Thompson daughter female white 3 6/12 single Texas

Jimmie R Thompson daughter female white 2 2/12 single Texas

"United States Census, 1930," index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:H2JN-3W2 : accessed 12 May 2015), Annie R Thompson in household of Charles A Thompson, Precinct 7, Van Zandt, Texas, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 0025, sheet 9A, family 176, line 28, NARA microfilm publication T626 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2002), roll 2405; FHL microfilm 2,342,139.

location: Ben Wheeler, Van Zandt County, Texas

date: April 15, 1930

Charles A Thompson head male white 26 married Texas farmer

Annie R Thompson wife female white 19 married Texas

Dorthy N Thompson daughter female white 3 6/12 single Texas

Jimmie R Thompson daughter female white 2 2/12 single Texas

"United States Census, 1930," index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:H2JN-3W2 : accessed 12 May 2015), Annie R Thompson in household of Charles A Thompson, Precinct 7, Van Zandt, Texas, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 0025, sheet 9A, family 176, line 28, NARA microfilm publication T626 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2002), roll 2405; FHL microfilm 2,342,139.

Annie Ruth Colley and Johnny L Fletcher marriage

location: Van Zandt County, Texas

date: June 27, 1968

"Texas, Marriages, 1966-2010," index, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VT5Q-54M : accessed 12 May 2015), Johnny Loranzer Fletcher and Annie Ruth Colley, 27 Jun 1968; citing Van Zandt, Texas, United States, certificate number 061762, Vital Statistics Unit, Texas Department of State Health Services, Austin.

date: June 27, 1968

"Texas, Marriages, 1966-2010," index, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VT5Q-54M : accessed 12 May 2015), Johnny Loranzer Fletcher and Annie Ruth Colley, 27 Jun 1968; citing Van Zandt, Texas, United States, certificate number 061762, Vital Statistics Unit, Texas Department of State Health Services, Austin.

Robert Clarence West - 1940 census

1940 census

location: Van Zandt County, Texas

date: May 1, 1940

R C West head male white 42 married Texas farmer

Ruth West wife female white 29 married Texas

Leland West son male white 19 single Texas

Dorthy Thompson stepdaughter female white 13 single Texas

Jimmie Thompson stepdaughter female white 12 single Texas

"United States Census, 1940," index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K4Q7-FGC : accessed 12 May 2015), R C West, Justice Precinct 7, Van Zandt, Texas, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 234-24, sheet 4A, family 64, NARA digital publication T627 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2012), roll 4155.

Monday, May 11, 2015

John Adams Research Paper

“Facts are stubborn things.”

When America’s Founding Fathers are thought of, many people automatically think of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and John Hancock. While they were great men with lasting contributions to our country, John Adams is sometimes overlooked in favor of the more famous Founding Fathers. It is important that today’s Americans remember Adams not only for his participation in the founding of our country, but also for his legacy in the American legal system. Adams’ virtuoso defense of the British soldiers charged with murder in what later became known as the Boston Massacre remains one of America’s supreme legal performances in history. The Boston Massacre trials launched Adams into Early National American politics, and laid a foundation for his belief in democratic government and liberty. This essay will briefly examine the events leading up to the Boston Massacre, the trial of British Captain Thomas Preston, and the trial of the British soldiers, all with Adams serving as the connecting cornerstone.

After the repeal of the Stamp Act in 1766 and the passage of the Townshend Acts in 1767, British troops were sent to Boston to attempt to keep order in the city (Zobel 65). Not only did the British soldiers patrol the city, many lived and worked part time in Boston warehouses and barracks. Because of the taxation and presence of British soldiers on the streets of Boston, riots and protests were common in those tempestuous times (John Adams Heritage Blog). Matters culminated on the night of March 5, 1770, on King Street in Boston. A lone sentry, posted in front of the Custom House, was being taunted by a group of men and boys. After a church bell started ringing (a signal for fire), the streets were suddenly filled with several hundred citizens. The sentry was reinforced by eight British soldiers and their captain. The crowd quickly began shouting, cursing, and throwing ice, snowballs, sticks, oyster shells, and stones at the soldiers (McCullough 65). One soldier, Hugh Montgomery, was struck twice, the second time so hard that he was knocked to the ground. With tensions rising, “Fire!” was heard and the soldiers began shooting at the citizens. When the smoke finally cleared, four citizens were shot dead and one more died five days later. Captain Preston was afterward remembered as furious that his men had fired a single shot without his order (Zobel 287). So who gave the command to fire?

The day after the shootings, the British soldiers began to seek legal representation. Given the sour taste of British relations, Boston attorneys did not want to represent the soldiers and their captain. After several tries at obtaining council, Josiah Quincy, Jr. agreed to assist in the representation under the condition that John Adams would join him (Donovan 23). “Adams accepted, firm in the belief, as he said, that no man in a a free country should be denied the right to counsel and a fair trial, and convinced on principle, that the case was of utmost importance” (McCullough 66). Robert Auchmuty created the triumvirate of the Captain’s defense team as he joined Quincy and Adams in the biggest trial any of the men had ever been involved (John Adams Heritage Blog).

Three weeks after the shooting, the British soldiers and their captain were indicted for the murder of the Americans, including the mixed-race mulatto Crispus Attucks (John Adams Heritage Blog). Waiting for tensions to cool, the trials did not begin until late-November. In the meantime, a propaganda war began. A committee in charge of submitting an official account of the murders produced a one-sided account, entitled A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre in Boston (John Adams Heritage Blog). The Narrative spanned an ocean in readership. In addition, Samuel Adams, a distant cousin of John Adams, co-authored another heavily prejudiced account of the shootings. Another example of this early-American propaganda war is Paul Revere’s poignant engraving of the massacre, notable for it’s lasting emotional significance. Within a few days of the shootings, a young man named Henry Pelham produced a dramatic drawing depicting the events on King Street on the night of March 5, 1770. Never mind that the drawing was grossly inaccurate, Paul Revere was somehow able to obtain, without permission or attribution, the drawing and engrave it for mass reproduction (Zobel 211). The engraving, coupled with heavily biased accounts of the shootings on King Street, fanned a flurry of anti-British sentiment. Adams later remarked that representing the soldiers and their captain caused him to be the target of “suspicions and prejudices” from the people of Boston (McCullough 66). Above all, Adams hated public scorn.

Adams and his team of two councilors immediately faced a dilemma that if not handled properly, could potentially cost Captain Preston and his men their lives. The problem arose from one major fact: Captain Preston had not killed anyone. He stood accused of ordering his men to fire without enough reason. Captain Preston needed to argue in court that he had never given a command to fire. On the other hand, the soldiers needed to show that in pulling their triggers, they had only followed orders (Zobel 241). Against some of the soldier’s wishes, Adams decided on the legal strategy of holding two trials, one for Captain Preston and one for his soldiers. John Phillip Reid has argued that John Adams separated the trials in order to prevent any mutual finger-pointing by either the soldiers or Captain Preston (Reid 196).

Captain Preston’s trial began on October 24, 1770, a mere seven months after the Boston Massacre (John Adams Heritage Blog). Until Captain Preston’s trial, no criminal case had ever required more than one day to try (excluding jury deliberations) (Zobel 248). Attorneys for the crown (the prosecution in modern terms) opened the case. The crown needed to prove that Preston gave the order to fire, or in the very least, could have prevented the shootings all together (Zobel 248). Over two days, the crown called fifteen witnesses alone who testified that they heard Captain Preston give the order to fire. However, on cross-examination their testimony appeared contradictory (ja historical society). If anything, the testimony of the crown’s witnesses strengthened the upcoming defense’s argument “that the crowd’s violence and taunting had provoked the tragedy” (Zobel 251).

Next, as junior attorney to the defense, John Adams was tasked with opening the defense’s case and questioning witnesses. No notes or transcripts remain of Adams’ opening, but his initial tactic was to set the scene of the event: a cold March evening, where British soldiers were being taunted and heckled beyond bearing, that finally culminated in the deaths of Boston citizens (Zobel 254). Calling twenty-two witnesses on day three of Captain Preston’s trial, Adams created a scene of confusion, noise, and verbal threats (Zobel 256). Adams did not call Captain Preston’s men to testify on his behalf even though they could have done so. Hiller B. Zobel points out that the men could have provided accounts that the townspeople had provoked the soldiers and Captain Preston was left with no other option that to command the soldiers to fire (Zobel 255).

Finally, on October 27, 1770, the defense rested (Zobel 260). Adams next rose to give his summation. Beginning the legendary summation Adams laid a framework rooted in law. “It is better five guilty persons should escape unpunished, than one innocent person should die” (Zobel 260). Following that, Adams dissected the crown’s evidence. With a legal finesse, Adams had an answer for the witnesses of the crown who claimed they had heard Captain Preston issue the order for fire: instead, townspeople had not heard Captain Preston’s entire command of “Fire by no means!” (Zobel 261). Whether truth or merely speculation, with this simple suggestion Adams was able to raise serious doubts of Captain Preston’s utterance of that infamous command. Adams also had an answer for the conflicts of evidence on who actually issued the order to fire. He argued that since the mob caused the soldiers to fire, then the mob could have also caused witness accounts to be unreliable (Zobel 262). Perhaps sensing defeat, the attorney for the crown who gave the prosecution’s summation, Robert Treat Paine, could barely be heard during the summation (Zobel 264).

On October 30, 1770, the jury returned with a verdict in the case of Captain Thomas Preston: not guilty (Zobel 265). John Adams had successfully defended his client, but now the work began to save Captain Preston’s men from execution. The Captain’s acquittal made the soldiers’ defense more difficult (Zobel 268). The crown had an easier time proving that the soldier’s acted on their own accord by firing into the townspeople.

Samuel Quincy led off for the crown in the trial of the soldiers that began on November 27, 1770 (John Adams Heritage Blog). With the five deaths that occurred as a result of gunshot wounds on March 5, 1770, the crown was faced with a much easier job by only having to prove that the soldiers were there and that they fire their weapons (Zobel 271). Unfortunately for the crown, several of its witnesses hit sour notes. One witness recalled that it was the townspeople who were yelling “Fire!” (Zobel 273). The majority of the crown’s witnesses testified to a crowd of armed sailors and missile-throwing boys attacking and possibly knocking down an armed soldier (Zobel 274).

As the crown’s case came to an end, Quincy kept his closing remarks simple. He named each soldier individually, and reminded the jurors of each witness who was able to identify each. He reviewed in explicit detail each witnesses testimony (Zobel 276). Quincy closed, “confident on the evidence as it now stands” (Zobel 277).

Junior attorney Josiah Quincy, and younger brother to the crown’s junior attorney Samuel Quincy, started the defense case for the soldiers. His job was to desensitize the emotions which the crown’s testimony was able to incite (Zobel 278). Not every citizen on King Street on the night of the shootings witnessed the soldiers acting out of hatred by firing on the citizens. In fact, the defense witnesses nearly all testified that the British soldiers were in real peril (Zobel 283). One witness specifically remembered seeing the now-dead Crispus Attucks reach into a woodpile and pull out two large clubs (Zobel 283). The defense’s climax came in the form of star witness Dr. John Jeffries. Dr. Jeffries was present on the deathbed of the soldier who died five days after the shooting (Zobel 285). According to Dr. Jeffries, the soldier stated that he did not blame the British soldiers for firing into the crowd. He seemed incredulous that the soldiers had not fired sooner than they actually had. Not only that, but the dying citizen did not blame the soldier who fired the bullet that would ultimately kill him (Zobel 286). This testimony wrapped up the defense’s case, powerfully aided the defense, and happened to be John Adams’ exact legal strategy (Zobel 284).

Unlike the first trial, Adams did not play the role of junior attorney. He did not call and question witnesses, but he did give one of history’s greatest speeches with his summation. Returning in part to strategy used in Captain Preston’s case, Adams again reminded the jury that innocence be protected at the expense of guilt being punished (Zobel 289). It is worthy to note that by conceding this point, Adams admitted to the guilt of at least some of the soldiers. Furthermore, Adams was faced with the problem of bloodshed. Eighteenth-century Americans were convinced that blood required blood. Adams reminded the jury of a time in Colonial American history where enemy forces had been slain, but colonists did not call for the blood of the aggressors (Zobel 289).

In another strategic move, Adams addressed the law of self-defense. Adams argued that if the mob had throated the lives of the soldiers, then the soldiers had a right to deprive the lives of the mob. Making an exact legal point, Adams posited that even if the killings might not have been entirely justifiable, still they were no more than manslaughter (Zobel 291). After making this point, court adjourned for the day.

The next morning, Adams turned to the evidence and testimony from the trial. He left no stone unturned as he examined each witness’s testimony in minute detail. Nothing escaped his attention. At no point did Adams explicitly call witnesses liars, but he inferred that given the mob mentality, it was no wonder that few of the crown’s witness’s testimony reliably matched. Regarding Montgomery, the British soldier who had been knocked to the ground Adams asked: “What could he do? Do you expect he should behave like a Stoick Philosopher lost in Apathy?” (Zobel 292). Adams closed his summation with his famous lines that “Facts are stubborn things.” He coasted to the finish by reminding the jury that the law is “deaf, inexorable, inflexible” (Zobel 293).

Finally, it was Paine’s turn to provide the summation for the crown’s prosecution. Almost comically, rather than establishing his own legal points, Paine refuted or denied the defense’s. Paine’s attempts were not enough. On the afternoon of December 5, 1770, the jury returned its verdict in the case of the Boston soldiers accused of the Boston Massacre. Six soldiers were found not guilty, while two soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter. Because they had never been in any legal trouble before, both guilty soldiers claimed benefit of the clergy, had their thumbs branded with an “M”, and were released (John Adams Heritage Blog).

John Adams’ successful representation of Captain Preston and his soldiers made Adams in the long run more respected than ever (McCollough 68). Just a short time later, Adams was elected to the Boston city legislature, an appointment which clearly indicates the respect the thirty-four-year old had earned the previous Fall (Zobel 298). The trials earned Adams much esteem not only in the courtroom, but in New England and abroad. His defense of liberty remains one of America’s greatest treasures.

Bibliography

Adams, John, and Frank Donovan, ed. The John Adams Papers. Cornwall, New York: The Cornwall Press, Inc., 1965.

McCullough, David. John Adams. New York: Touchstone, 2001.

Reid, John Phillip. “A Lawyer Acquitted: John Adams and the Boston Massacre Trials.” The American Journal of Legal History, Vol. 18, No. 3 (Jul., 1974). pp. 189-207.

The John Adams Historical Society Blog; “Events that led to the Boston Massacre.” www.john-adams-heritage.com/events-that-led-to-the-boston-massacre/ (accessed May 4, 2015).

Zobel, Hiller B. The Boston Massacre. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, Ltd, 1970.

Saturday, May 2, 2015

Book Review: Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market

Walter Johnson’s Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market provides an incredibly in-depth look at the interstices of Antebellum slave pens, mainly those in New Orleans, Louisiana. He examines the daily activity of the slave pens, from the perspective of all participants: the slaves, slave buyers, and slave sellers. Johnson demonstrates how the sale of human beings was a complicated process and he guides readers through the motions of the typical transactions. While many historians focus on the plantations as the center of slave life, Soul by Soul provides a new perspective with the slave pens taking center stage in the history of the antebellum South.

To begin, slave narratives played a dominant role in the evidence used by Johnson to recreate the slave pens. Johnson cited three strategies he employed to decipher the three versions of the slave pens: slave narratives read in tandem with sources produced by slaveholders and visitors to the South; slave narratives read for traces of the experience of slavery antecedent to the ideology of slavery; and the slave narratives read for symbolic truths that stretch beyond the facticity of specific events. In short, Johnson did not solely rely on the words of former slaves themselves, but instead analyzed the slave narratives while fact-checking with other versions of the same story (10). In addition, judicial records were an invaluable source, even though slaves themselves were never allowed to physically testify in a court of law (11). Many slaveholders communicated in letters to family and acquaintances about the intricacies of slavery, and Johnson combed through these for correlations (13). Relying on the most “chillingly economical descriptions of slave sales,” Johnson used the notarized Acts of Sale to reconstruct a historical point of view (14). Truly, no stone is left unturned in Johnson’s rendition of the transaction process within slave pens.

Johnson brings into sharp focus the human reality of the Southern slave trade by explaining the chattel principle. “Any slave’s identity could be disrupted as easily as a price could be set and a piece of paper passed from one hand to another” (19). Slaves were dehumanized based on the price they would bring at a slave sale. These humans had a value that could be abstracted from their bodies and cashed in when the occasion arose (26). Children were not exempt from this facet of chattel-life, either. In fact, Johnson argues that the bodies of slave children were forcibly shaped to their slavery (21). Whippings were designed to correct slave children’s deficits in “character”, or their vices. These slave children would have lived in daily fear of being separated from their families and sent to a slave pen.

One of the most interesting facets of Soul by Soul is Johnson’s claim that antebellum whites used slavery, slave ownership, and slave auctions to assert themselves into Southern society. Undoubtedly, slaveholders were looked upon by their contemporary antebellum counterparts as the elite social class of the time period. In general slaveholders had more money, more property, better housing, more luxury personal items, and more slaves than any other social group. Many slaveholding men and women viewed slave ownership as an indicator of wealth. Johnson’s example of a probable newly-acquired slaveowner aboard the steamship F. W. Downes is a perfect example of slaveholders using slavery as a means to climb the antebellum social ladder. A Mr. J. B. Alexander was witnessed frantically shuttling around the steamship bragging about his recent purchase of “negroes.” Johnson claims that “one of the ways white men made friends with one another was by talking about the slaves they had just bought or sold” (198). White men would also judge other white men on their supposed ability to purchase worthy slaves. Again aboard the F. R. Downes, Mr. Alexander was judged to have made a poor business decision. “When he boarded the F. R. Downes with his new slave, a man he did not know walked up and “remarked to him that he had bought a dead Negro” (201). Slaveholders daily gambled their own fantasies of freedom on the behavior of people whom they could never fully commodify (214).

In addition, slaveholding women were not to be left out of projecting a higher social class based on their ownership of slaves either. One woman had her twelve-year-old slave beaten when his nose dripped blood on dinner napkins (206). A slave’s bloody mess would have been mortifyingly embarrassing for a white woman.

Soul by Soul hits its stride when Johnson explores the various ways in which the slaves themselves were sometimes able to subtly control their own destinies. Historically, slaves in a slave pen have been looked upon as helpless when it came to their sale or salability. Johnson contends that slaves would intentionally try to manipulate slave buyers and sellers. Some slaves used their own skin color to resist slavery. Johnson provides the story of Robert, a light-skinned slave who boarded a steamboat out of New Orleans and escaped slavery. His fellow passengers thought he could have been of Spanish origin. Robert’s skin color, along with his general comportment, allowed him to pass into white society and out of slavery. Another slave, Alexina Morrison, was described as being too white to be a slave. Her blue eyes and blonde hair helped as well. Alexina was able to escape her buyer and sue him for her freedom in the courts of Louisiana. “One after another, her supporters came into court to testify that she was white in ‘her conduct and her actions’ (156).

Furthermore, Johnson points out that slaves were the people with the information. “Slaves were the information brokers in the slave market” (176). Slaves knew what the traders wished them to say and what the holders wished to hear. Sickness would have been the easiest form of resistance many slaves could carry out. Slave buyers had an eye out for even the smallest signs of illness in slaves. “Buyers were searching for vitality and responsiveness” (178). Rather than constant acts of rebellion, slaves used subtle, calculated methods to resist the “peculiar institution.”

Many slaves were bought on a trial basis. This would have provided some with an excellent opportunity to feel their new slave holder out for temperament, anticipated abuse or lack thereof, and general welfare, as well as allowed the buyer to determine if they had made a smart purchase. An advertised cook could have decided to cook poorly. Johnson speculates that one slave, Daniel, may have faked his deafness in order to be brought back from Texas to New Orleans. Johnson also argues that purchasing slaves on a trial basis gave white women an opportunity to participate in the slave trade. Though not able to accompany men to the slave pens, if bought on trial slaves could be brought home and tested out (182).

Soul by Soul brings back to life the New Orleans slave market. As the largest slave market in the South, New Orleans served as the shining example of slave pen life. What Walter Johnson is able to recreate is a testament to his intensive research and his exemplary writing ability. Soul by Soul is a balanced and readable account of America’s most shameful days. I highly recommend!

Friday, May 1, 2015

W. R. Bonner - obituary

December 23, 1930

W. R. Bonner, 95, Dies.

Special to The News

CORSICANA, Texas, Dec. 23. - W. R. Bonner, 95, resident of the Phillips Chapel community for many years, and native of Tennessee, died Monday night and the funeral services were held Wednesday afternoon with burial in the Hamilton Cemetery. Several children survive.

Source: Corsicana Daily Sun, Tuesday, December 23, 1930, page 13.

W. R. Bonner, 95, Dies.

Special to The News

CORSICANA, Texas, Dec. 23. - W. R. Bonner, 95, resident of the Phillips Chapel community for many years, and native of Tennessee, died Monday night and the funeral services were held Wednesday afternoon with burial in the Hamilton Cemetery. Several children survive.

Source: Corsicana Daily Sun, Tuesday, December 23, 1930, page 13.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)